In October 2016 Peter Loo travelled to Rojava*

to volunteer as an English teacher and participate in work within civil

society – the outcome of over 14 months of organising within the Plan C

Rojava solidarity cluster. He is currently working for the SYPG campaign in Qamishlo.

As well as directly offering his skills Peter has been able to visit

places in Rojava and speak to many people as the future of Rojava, and

Syria in general, continues to hang in the air. This interview took

place late in December 2016. First published on Novara.

Hi Peter, we’ve got lots of questions about your experiences so

far but perhaps you could explain a little about the history to date for

some readers who might not know too many of the details.

Well, we should start by briefly talking about the origins of the

revolution. Many people skip over this part but it is vital to

understanding the dynamics of the whole revolution. The Democratic Union

party (PYD) who led the revolution have been active in northern

Syria/western Kurdistan (Rojava is the Kurmanji word for west) since

2003. Before them the Workers’ party of Kurdistan (PKK), who the PYD are

affiliated to, were permitted by the regime to use the region as a base

to organise against the Turkish state until they were ejected in 1998.

The first protests against [Syrian

president Bashar al-] Assad started in early 2011 and by the spring the

PYD had begun to focus effort into organising the Kurdish community,

forming local committees and armed self-defence units (the precursors to

the YPG and female YPJ forces).

This was to be the social basis for the revolution. In the middle of

July in 2012, as the social movement against Assad turned into a bloody

military conflict involving many international powers, these

self-defence forces, bolstered by PKK-trained guerrillas, evicted the

regime from several towns and cities in the north. The PYD’s defence

forces took control of major roads and evicted the regime forces from

key infrastructure sites with very few clashes or casualties.

The uprising had a distinct geography: areas with a predominant

Kurdish population where the PYD had been organising were the ones to

rise up and eject the regime forces. In areas without an overwhelming

Kurdish majority, Assad’s forces managed to maintain a presence. Here in

Qamishlo, where an estimated 20% of the population support the regime,

there was some heavy fighting but the regime managed to hold onto many

of the public buildings. July 2012 marks the emergence of Rojava as a

distinct force in the Syrian conflict. The cantons which were formed

declared themselves to be against Assad (though arguing that he should

be removed through elections not force), yet not a part of the rapidly

fragmenting constellation of Syrian rebels. The relationship between

Rojava and the Free Syrian Army (FSA) – the military forces initially

formed by the rebels – is a complicated one and there have been examples

of both co-operation and conflict between Rojava and different parts of

the FSA since the beginning of the revolution.

This account of the origins of the

revolution as an insurrection is contested by those more critical of the

Rojava revolution and its refusal to join the wider uprising against

Assad. Most publicly in the UK these critics include Robin Yassin-Kassab

and Leila al-Shami, the authors of Burning Country.

In this book, which only briefly touches on Rojava, the authors argue

the withdrawal of Assad’s forces was “apparently co-ordinated” with the

PYD, whose coming to power was a fait accompli, agreed beforehand with

the regime in order to free troops up from guard duty to fight the

rebels elsewhere. These two narratives (fait accompli or successful

insurrection) clash and I don’t have a definite answer – perhaps things

will become clearer in the next few months as the future of Rojava’s

relationship with the regime becomes apparent. However the fait accompli

argument doesn’t explain why there were military casualties in the

initial days, nor why hostilities continue sporadically. A conspiracy

doesn’t seem that likely. Rather, [it’s likely that] recognising the

political reality in Rojava had changed with the insurrection, Assad

renegotiated his political position with regards to this part of Syria,

possibly keeping his options open in the long term.

From this beginning the revolution

has expanded geographically – two of its three cantons are directly

connected (Kobane and Cizire cantons), and fighting continues to connect

these to Efrin canton – and also socially. A political system based

around decentralisation (the confederal system) and the construction of

local-level ‘communes’ has been instituted, an economic system which

prioritises co-operatives and provides for the people’s basic needs is

in place, and a massive shift in gender relations is under way. This is

one of the most exciting political struggles

being undertaken in the world today both in terms of its scale and

scope, made all the more impressive given the conflict continuing to

unfold in Syria and the hostility it faces from neighbouring countries.

We’ll come back to the revolution’s relationship with the regime

later on. So the revolution began as a PYD-led movement, primarily

supported by Kurds?

Exactly. After what we could call the insurrectionary phase of the

revolution – removing the regime from effective control – the next phase

was one of political consolidation and the implementation of a

political programme. This programme has three central planks: a system

of grassroots democracy (which exists in a relationship with formal

political parties and some form of representative system) which goes

under the name of democratic confederalism, a women’s revolution, and an

ecological programme (by far the least developed aspect at the moment).

Building support for this programme beyond both the PYD and the Kurdish

community were the immediate tasks of the revolution.

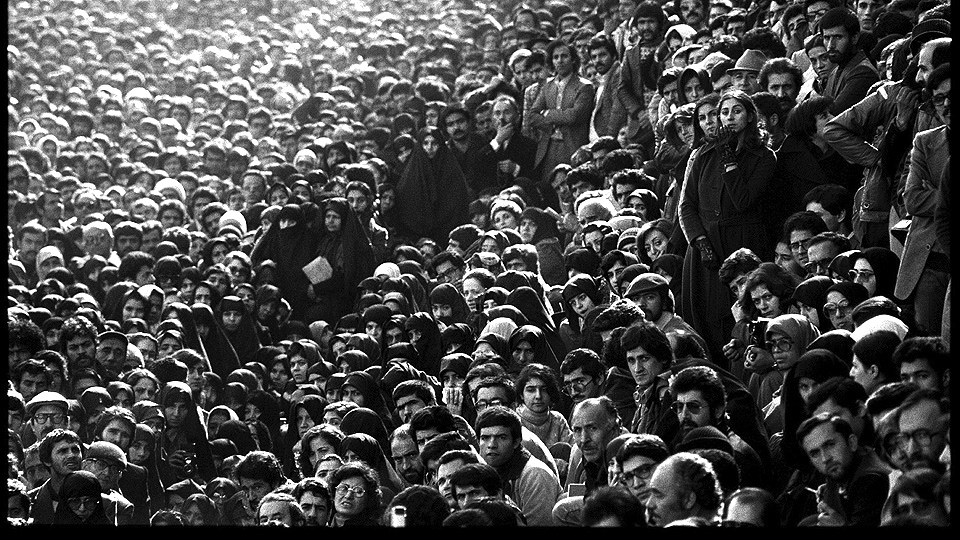

celebration of the anniversary of the confederal system.

Many smaller political parties are now an active part of the revolution, working together beneath the umbrella of TEV-DEM (Movement for a Democratic Society).

But obviously not everyone is supportive of what is happening. ENKS, a

coalition of 16 parties dominated by Massoud Barzani, president of the

Kurdish regional government (KRG) of Iraq, has been a vocal opponent of

many of the developments here in Rojava. Barzani does not share the

political vision of the PYD, modelling KRG on oil states like Dubai, and

is currently implementing a full embargo on Rojava alongside his ally

Turkey which is causing all kinds of problems. Because of these tensions

Carl Drott from the University of Oxford has argued that “sometimes it

seems that the only consistent policy of the KCN [ENKS] is to oppose

anything that the PYD does.”

More importantly the revolution has

prioritised gaining the trust and support of all the communities here in

Rojava. These communities (Arab, Syriac, Chechen, Armenian, Turkmen,

etc.) are participating in increasing numbers as time goes on and they

see the ideas of the revolution – and its benefits – put into practice

as well as seeing that the regime isn’t coming back. The reasons for

supporting the revolution vary from the more politically motivated, such

as a desire for a free Kurdistan or a belief in the politics of [the

PKK’s imprisoned leader Abdullah] Öcalan

and his vision of confederalism, to the less abstract desire for peace,

security and the provision of basic services which the revolution is

providing. The YPG and YPJ are pretty much universally loved here and

this support has extended to the military alliance – the Syrian

Democratic Forces (SDF) – they have built with other progressive

militias (of different ethnicities) in the region.

The revolution began from within the

Kurdish community and work to build support for it within other

communities is a central priority. This includes working with the

thousands of Arab refugees fleeing the conflict in the rest of Syria who

are being blocked from travelling to Europe by the Turkish state. Part

of my work with TEV-DEM

here centres around building this support across communities. The

Syriac community, for example, is starkly divided between the regime and

revolution, with each faction possessing its own military and police

units. Passing through the Syriac neighbourhoods these division are

quite clear, one street full of portraits of Assad and the regime’s

flag, the next containing pro-revolution checkpoints with revolutionary

slogans on the walls.

Let’s tackle the thorny question of the relationship between the regime and the PYD. In short, what’s going on?

Well, as I said earlier, the revolution didn’t kick the regime out

everywhere. Here in Qamishlo, the regime still has a presence. When

Aleppo was ‘liberated’ recently for example, there were loud, noisy

celebrations for Assad’s victory in some neighbourhoods and the regime

still pays the salaries of some civil servants like teachers.

Occasionally clashes break out in the cities where the regime still has a

presence such as Qamishlo and Hasseke.

As I said earlier the revolution here has constituted itself as a

force independent of the wider rebel movement against Assad (itself very

diverse). It has relied on the support of international social

movements, progressive political parties, and also most controversially

on the support of large states such as the USA and (at times) Russia.

These have to some extent prevented Assad or, more likely at the moment,

the Turkish state from outright crushing them, but the situation is

still perilous. With regards to the regime, it’s unclear at the moment

how the regime will orientate itself towards Rojava and vice-versa. At

the moment, neither side has the outright military strength to easily

defeat the other. With the defeat of the rebels basically being assured

with the re-occupation of Aleppo this might all change. For example, the

YPG and YPJ in the large Kurdish neighbourhood of Aleppo, Sheiq

Maqsoud, who defended it from rebel attacks (and also aided Assad’s

forces at some points in the fighting) have now pulled out, only leaving

Asayish (armed police) in the neighbourhood.

This ‘relationship’ with the regime has been criticised by many. At

the start of the Syrian uprising the potential for a broader alliance

between Kurds and Arabs seemed possible but failed for a variety of

reasons. These include a latent Arab chauvinism, a by-product of decades

of colonial rule in Rojava by the regime which was one factor in the

unwillingness of both the regime and the rebels to see Kurdish autonomy

established. The rise to pre-eminence of Islamist forces on the rebel

side also blocked a wide-scale alliance between the Rojava revolution

and the rebels. Alliances have been made with forces in the regions that

make up the cantons, the SDF for example, but a broad alliance with the

larger factions on the rebel side did not come about. This missed

alliance, if it was ever possible, has probably significantly shaped the

outcome of the rest of the conflict.

We have seen a rapid expansion of the Rojava cantons, particularly

into areas with a sizeable Arab population. Could you tell us about

your experiences of how the different ethnic groups are accommodated

into the revolution, and how it has been received?

Since 2015 the areas controlled by

the cantons have expanded massively through their offensives against

Isis. It’s undeniable that one reason for this is to build a continuous,

connected system of cantons. These offensives, by a primarily Kurdish

military into primarily Arab areas, have thrown up some problems. I had

the opportunity to visit the front at Salouk in December. As the Raqqa

offensive pushed the front lines further forward people were being

allowed to return to their villages. In the main the villagers I met

seemed broadly supportive of the SDF forces they came into contact with.

However, not all the villagers support what is happening – many, we

were told, had been or still were supporters of Isis. We visited one

Tabur (military unit) which had been the victim of a suicide attack

earlier in the year; the attacker was a frequent visitor from the

village next door.

As the area controlled by the confederal system has expanded, changes

have taken place to accommodate the increasing numbers of non-Kurdish

participants. I’ve mentioned the SDF as a multi-ethnic military

coalition, which marked a positive step forward for the revolution. The

current official name of the region, the Democratic Federal System of

Northern Syria, is an indication of the multi-ethnic project the

revolution is trying to build. We saw one of the co-chairs of the

confederal system, Mansur Salem, who is a Syrian arab, speak a while

back and he was stressing how building this multi-ethnic support is a

key political challenge for the revolution.

To what extent is the ideology of the revolution in Rojava being taken up by ordinary people?

Visitors arriving in Rojava expecting

some kind of transcendental revolutionary experience will be

disappointed. Given the amazing work that is happening, and all the

great media being produced for western audiences this isn’t surprising,

but beyond the front the way the revolution is manifesting itself can

often be quite subtle or even not as developed as one might expect or

hope.

I’ve already mentioned the fact that

spreading the values of the revolution into other communities is a work

in progress. As another example, whilst the higher levels of the

confederal system, especially in cities, are well developed, the lowest

level, the commune –

a neighbourhood level institution in which the most direct

participation in political assemblies and politically-themed committees

takes place – is not as widespread as one might think from the outside.

The reasons for this come back to the origins and dynamics of the

insurrectionary phase of the revolution as discussed earlier.

Counterintuitively, we have the higher levels of this political system

actively trying to expand the grassroots level of political

participation. Lots of work is taking place to expand the numbers of

communes numerically and geographically. It requires finding physical

resources and educating people in the local community about the values

of the revolution and the way the (sometimes complicated) systems work

here. But perhaps the most visible element of the revolution is the role

of women in society here.

That was going to be my next question. The image often projected

of the revolution emphasises women’s liberation and the role of the YPJ

in leading the call to change gender relations. How much does this

impact on daily life in Rojava, and is it really such a fundamental part

of the movement?

A criticism from the left in Europe, as exemplified in a recent article by Gilles Dauvé,

is that the women’s revolution in Rojava is limited to the women in the

YPJ. If it were then Rojava could not be seen to be having a women’s

revolution. After all, the Israeli state conscripts female soldiers and

[Muammar] Gaddafi was famous for having female bodyguards. History is

littered with examples of women playing a significant role in social

struggles or military conflicts, only to be returned to subservient

social positions at the ending of hostilities. But this isn’t where the

women’s revolution stops here in Rojava. Neither does it stop at the

point of ensuring 40% women’s representation in all committees and an

equality of speaking roles (alone a step beyond most western states).

Underpinning all these clearly

visible outcomes is the slow, patient development of the women’s

political movement: political education for women to develop their

skills and build the confidence of future organisers, forms of

(re)education and intervention against abusive men, the activity of

women’s committees at all levels of the confederal system, and the

tireless work of the Kongreya Star (star congress) – the organised expression of the women’s movement here.

Once again, this isn’t a problem-free process; these changes are

being built upon a hugely conservative society where violence against

women, honour killings, forced marriage, an incredibly huge pay

differential, as well as the more humdrum features of patriarchy were

all extremely common before the revolution. The movement is working hard

to bring everyone with them, to be firm and take immediate action where

needed or to take a more long-term approach where this is more

effective.

Like everything here, it shares many

features with western movements but retains many differences. The

political underpinnings of the women’s movement here are collectively

called Jineology,

which means the science of women. Öcalan is, unsurprisingly, a key

jineological theorist and has laid out a broad argument about the

historical roots of patriarchy which overcame a peaceful matriarchal

society. Capitalism is seen as inherently patriarchal and Öcalan, who is

once again the key reference point for the movement, argues “the need

to reverse the role of man is of revolutionary importance.”

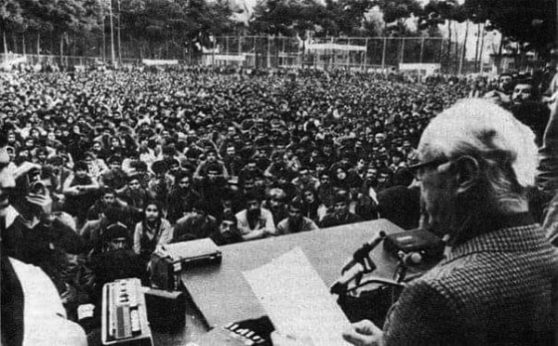

First young women’s conference in Cizire canton.

But some parts of this theory will be

more problematic for some feminists in the west. For example, the

Jineological approach to gender seems to be an essentialist one where

definite characteristics are assigned to the genders. Queer feminists

will find this ideology quite challenging. The politics of sexuality are

also quite different than in the west, for cadre sexual relations are

pretty much forbidden and in the rest of society there is a strong

emphasis on abstinence until marriage. In many interviews when queer

sexuality is raised the standard answer seems to be something along the

lines of ‘we’ve never met a gay person in Rojava before’. However this

is something which will hopefully be addressed as time goes on, and I’ve

heard reports of public lectures on LGBT politics taking place in some

areas.

That’s a good point about Jineology not mapping onto western

feminism directly. Could this be said about Apoist movements in general?

Yeah, definitely. Lots of debates

about the PKK built on answering the question ‘are they an anarchist

organisation?’ have gone around in circles because they have failed to

actually analyse the movement itself. In the same way the PKK was never a

straightforward Marxist-Leninist organisation historically, it isn’t an

anarchist movement today. The PKK and its sister organisations

self-define as ‘Apoist’ – a movement built around Abdullah Öcalan and

his, well, quite eclectic work. The movements based on his political

vision are contradictory, especially since the development of the ‘new

paradigm’ since Öcalan’s arrest in 1999. This paradigm significantly

changed many parts of the PKK’s political vision. Although the PKK has

now formally renounced the desire for an independent Kurdish state and

replaced it with its model of democratic confederalism, it is still a

hierarchical movement with strict discipline for cadre and a cult of

personality around Öcalan himself. Its conception of revolution doesn’t map onto those conceptions held by classical revolutionary movements, being:

“…neither the anarchist idea of abolishing the whole state

immediately, nor the communist idea of taking over the whole state

immediately. Over time we will organise alternatives to each part of the

state run by the people, and when they succeed, that part of the state

dissolves.”

Quite importantly its critique of

capitalism, or capitalist modernity in its own terminology, whilst quite

opaque (an opacity which isn’t helped by the lack of movement works

translated into English) certainly isn’t as fundamental as those coming

from the Marxist tradition. Whilst the Apoist movement corresponds with

many of the values of socialist and anarchist traditions it is something

distinct and different.

There was an article by two other international volunteers

who self-define as anarchists on the Plan C website a short while ago.

The article makes some useful and important points about the complicated

practicalities of showing solidarity here and for that it should

definitely be read. They make the (uncontroversial) point that working

in Rojava is not neutral. The choices of who and how we work with here

will strengthen some groups, individuals and dynamics rather than

others, and we need to be aware of this.

I read this as making the implicit

argument common to many on the anti-authoritarian left to support the

people or the social movements rather than organised parties. A

particular problem with that perspective here is that the Apoist

movement has transcended the boundaries of its political parties and is

also a mass social movement with elements of self-organisation beyond

the parties. I’d argue that the revolutionary left needs to be

supporting the PYD and Apoist movements across the Middle East rather

than some loosely defined, potentially fictitious unaligned ‘people’.

They are a very large, possibly the largest, progressive force in the

Middle East and a large part of their politics resonate strongly with

our own. Demonstrating a serious commitment to real solidarity work,

which once it moves beyond writing articles starts to become very

challenging, helps to build the platform from which to engage in

discussion with these movements. There are parts of the Apoist vision

which I’d love to critically debate with them (for instance definitions

and critiques of capitalism) but this will probably only happen

meaningfully when one can demonstrate a track record of sorts.

Going back to the communes, how important are they?

At the local level they are important for solving small problems,

highlighting big ones, and function as the most local transmission belt

of the ideas of the revolution. As well as running the local meetings

and committees, the lower levels of the system serve as centres to

mobilise people for self-defence or for demonstrations and rallies. When

we go to political events we usually leave in large convoys of buses

from our neighbourhood’s Mala Gel (People’s House – basically a social

centre) and when we organise events the local communes are a vital

resource for directly connecting with people. I haven’t seen enough of

this quite complex system to judge to what extent the ideas from the

base of this system are listened to higher up the federal system through

the various elected delegates and thematic committees.

It’s quite funny, I met a European Marxist-Leninist here who was

convinced the anarchists had got the entire revolution wrong and that

the communes had a very peripheral role in what was going on. For him,

the revolution was dominated by the PYD with the YPG and YPJ providing

the muscle behind it. When he met one of the international Marxist-Leninist parties

here doing consistent community work promoting and actually setting up

communes his whole attitude completely changed. Perhaps some on the left

are a bit optimistic about how developed the commune system is but it

definitely exists and is growing, we just shouldn’t confuse our desires

with reality.

The Economy Question: One of the most important questions for many on the left is what kind of economy is being built?

Northern Syria was historically deliberately underdeveloped by the

Syrian regime and treated like an internal colony. Arab settlers were

encouraged to move into the region and alongside the exploitation of oil

reserves found in the area, the other main sector, agricultural

production, was strictly managed. What is now Efrin canton had its many

forests replaced with olive plantations whilst in the 1970s the regime

spread the rumour that a particularly vicious tomato blight was

spreading from Turkey in order to encourage the conversion of

agricultural production in Cizire canton completely to wheat. In winter,

driving through the endless empty fields which make up the countryside

in Cizire canton is quite a bleak experience. Efforts are now underway

to diversify agricultural production for both ecological and economic

reasons.

So the revolution did not inherit

much in the way of large scale means of production. The few large

productive sites that exist have been socialised. I think these are a

concrete factory, the oil wells, and, since the Manbij campaign, the

Tishrin dam. Here in Qamishlo there are about 60 ‘factories’ with a

maximum size of 20 employees. Some of these are private initiatives,

some run as co-operatives. The commercial and logistical side of life in

Rojava is also on the small scale. When the regime was evicted there

was little in the way of large scale logistics systems – transport

systems, or the integrated logistics systems large supermarket chains

possess – which could be socialised. The tiny rail system is out of

commission and the regime holds the airport in Qamishlo, which only

hosts an infrequent internal route to Damascus.

In a great interview by Janet Biehl, the adviser for economic development in Cizire canton discusses the ‘three economies’

functioning in parallel in Rojava. You can read about it yourself but

in short these are the ‘war economy’, the ‘open economy’ (i.e. the

private economy) and the ‘social economy’. At the moment the war economy

– subsidised bread and oil for example – dominates with the social

economy of co-operatives being pointed out as a future hope. Obviously

the danger is if/when the embargo is lifted and private investment is

allowed in – especially for expensive infrastructure like oil refineries

and heavy industry – that the social economy is completely outcompeted.

I wouldn’t want to venture a

prediction about the future of the economy here, though the future

challenges seem quite clear, but I can say it’s disappointing that some

on the left aren’t supporting what is happening here because of the

persistence of private property, commodity production and the wage

relation. This is a kind of ‘all or nothing’ purism which often comes

from such an abstract place, seemingly removed from an acknowledgement

of the difficulties of actual social change. No revolution so far has

managed to abolish capitalist relations – let alone in the space of a

few years, during an international proxy war, whilst also under embargo!

Whilst the Apoist critique of capitalist modernity is certainly not a

Marxist one, here in Rojava its economic strategy is broadly a

progressive one – albeit with question marks over the future – which

deserves our solidarity.

To withhold support because

capitalism will still function in some form for the foreseeable future

seems short-sighted. It’s interesting that we often support

non-communist social struggles right up to the point that they attain

the ability to significantly change the world, at which point many of us

withdraw our support. We need to take a longer term view of social

change which recognises it as a contradictory and complicated process.

Just because the revolution here isn’t immediately implementing

communism doesn’t mean we shouldn’t support it.

What is the dominant political make-up of international

volunteers? What kind of expectations do they come with, and in what

ways are those confirmed or subverted?

In general, the people who arrive

here are a mixture of the starry eyed and those expecting something a

bit more realistic. At one point, based on internet coverage alone, it

seemed as if the majority of volunteers were adventurers, well-meaning

liberals, or even more right-wing people just here to fight Isis. But

whilst this might have been the case at one point it certainly isn’t

now. The YPG has noticed the problematic views and behaviours of some of

its volunteers and has started to be more selective when it comes to who is volunteering.

Unsurprisingly, there are many

volunteers from the Kurdish diaspora but beyond this the majority of

volunteers I’ve met or heard about here are leftists. There is a

relatively large presence of Turkish comrades from Marxist-Leninist and

Maoist organisations for example. The other volunteers here are mainly

from Europe and north America, and the majority are in military units.

This includes a dedicated international Tabur – the International Freedom Battalion – people at home have probably seen some of the great pictures from their English-speaking ‘Bob Crow Brigade’.

Due to language barriers, and the

difficulties of travelling here and finding a placement where one can be

useful, there aren’t that many international volunteers in civil

society. Hopefully this will get easier as time goes on. At the moment

if people want to volunteer here they should think about what skills

they have or can get before they travel. For example, if people are

interested then training up to be an ESL (English as a secondary

language) teacher is a great way of being useful here as the demand for

lessons is very high.

What do you think the presence of international volunteers adds to the movement?

Sometimes specific skills which are

in high demand here, medical staff for instance. If not, at the very

least volunteers work as a link between Rojava and the rest of the

world. The people here know they aren’t alone and the rest of the world

gets to find out a little more about what is happening. This is

obviously a big responsibility for those with the ability to report back

and portray an entire revolution based on their experiences. Those of

us doing this need to try to be honest about what we’ve seen, what we

think, and the limits of our personal experience.

It’s not surprising but it is

disappointing to see criticisms of the majority of volunteers as

‘orientalist adventurers’, ‘closet islamophobes’, or ‘fantasists with a

hero complex’ which have arisen in some parts of the left. Whilst a few

people do fit this bill, most volunteers – especially politically active

comrades who have responded to calls to volunteer – aren’t like this at

all. The YPG is also now taking steps to filter those kinds of

volunteers out. It’s quite astonishing how even what I’d call an

uncontroversial historical value of the communist movement –

internationalism – is coming under fire from those who also see

themselves as part of the left. It feels like there are more left

volunteers from pre-existing structures here now, or perhaps they are

just using media channels more effectively. Either way, hammering home

the point that this is a progressive struggle which is demanding the

support of the international left and which sees itself as part of an

international movement is massively important and is a political task we

can all be involved with.

What do you think has been the most significant impact of the revolution so far?

For the people of the region the

revolution has liberated them from the domination of the Assad regime

and Isis. It has also made massive progress in terms of women’s

liberation and direct democracy. Internationally the revolution has

given a massive boost to the struggles north of the border in Bakur and

Turkey and to revolutionaries further afield. Although we need to be

cautious, there are many lessons we can learn from this revolution. At

the very least Rojava serves as a reminder that revolution is always a

possibility where revolutionaries are organised, committed and prepared

to risk their lives.

Our two volunteers in Qamishlo

Any final comments?

The revolution here does not map onto

the perfect fantasy of some revolutionaries in the west. It wasn’t the

spontaneous uprising of the overwhelming majority of the people, they

haven’t abolished the state (if that is ever possible) or capitalism,

and there are still problems to be solved. Despite the fact that this

isn’t full communism right here and right now, this revolution needs to

be applauded and supported. Like all revolutions, this one has not

emerged fully formed but is being built on the fly in the face of much

opposition. Unlike many revolutions this one is quite hard to define:

labels like ‘anarchist’ or ‘stateless revolution’ obscure more than they

reveal. What we do know is that this revolution is pushing forward

forms of popular democracy, women’s liberation and some form of

solidarity economy. Life in Rojava is better for more people than most

parts of the Middle East.

For those afraid of revolutionaries

having real power to make change rather than maintaining ‘resistance’

forever, I’d like to quote Murray Bookchin (whose influence on the

struggle here is definitely overstated in certain quarters).:

“Anarchists may call for the

abolition of the state, but coercion of some kind will be necessary to

prevent the bourgeois state from returning in full force with unbridled

terror. For a libertarian organisation to eschew, out of misplaced fear

of creating a ‘state’, taking power when it can do so with the support

of the revolutionary masses is confusion at best and a total failure of

nerve at worst.”

Those taking an ultra-left position

on Rojava, and rejecting it out of hand, show us more about the

weaknesses of their own politics than of the revolution taking place

here. A real revolution is a mass of contradictions which must be fought

through. That the revolution is doing that here without resorting to

the dictatorship of one political party makes this a particularly

important revolution for the libertarian left to be supporting.

There are more ways for the left to

express solidarity with Rojava, and the wider struggle it is part of

here in the region, than writing articles or sharing things on Facebook.

Getting information out about what is happening here is important of

course, but the obligations for political organisations who support the

revolution here, and who have the capacity, must be much higher. For

example in the UK Plan C’s Rojava solidarity cluster works with

Kurdish-led structures organising discussions and demonstrations, has

raised money for things like a school bus and medical supplies, and is

now sending volunteers for civil work.

There are a few hardworking Kurdish

solidarity groups in the UK also doing great work. When compared to

long-running solidarity campaigns, like the Palestinian solidarity

campaigns for instance, Kurdish solidarity campaigns are still in their

infancy in the UK. The massive intensification of Turkey’s

counterrevolutionary role both within its state borders and beyond,

potentially spilling into Iraq this year, make this solidarity even more

important. Effective national solidarity structures need to be

established or joined, and federated together internationally. It’s a

bit cliched but we can’t forget the slogan ‘solidarity isn’t a word,

it’s a weapon’.

Peter Loo is a member of Plan C and is active in its Rojava solidarity cluster. His statement is here. His other most recent report can be read here.

* ‘Rojava’ is used instead of the

Democratic Federal System of Northern Syria – the area’s official title –

as both a shorthand and as the name many in the west are more familiar

with.